Exposure Without A Camera

/Ron Saunders

Photographic Artist

I came across Ron and his artwork at a community market. I was actually at the market to check out all the vendors and see if I can put together a group of neighborhood restaurants and artists for an upcoming event centered on food justice in San Francisco's Bayview/Hunter's Point area. Earlier that week, my friend Nancy told me about a neighborhood artist I should reach out to, whom is also part of a collective of black artists called the 3.9 Collective. Not knowing what he looks like or even making any initial contact, we met while we were both talking to folks tabling about a community garden.

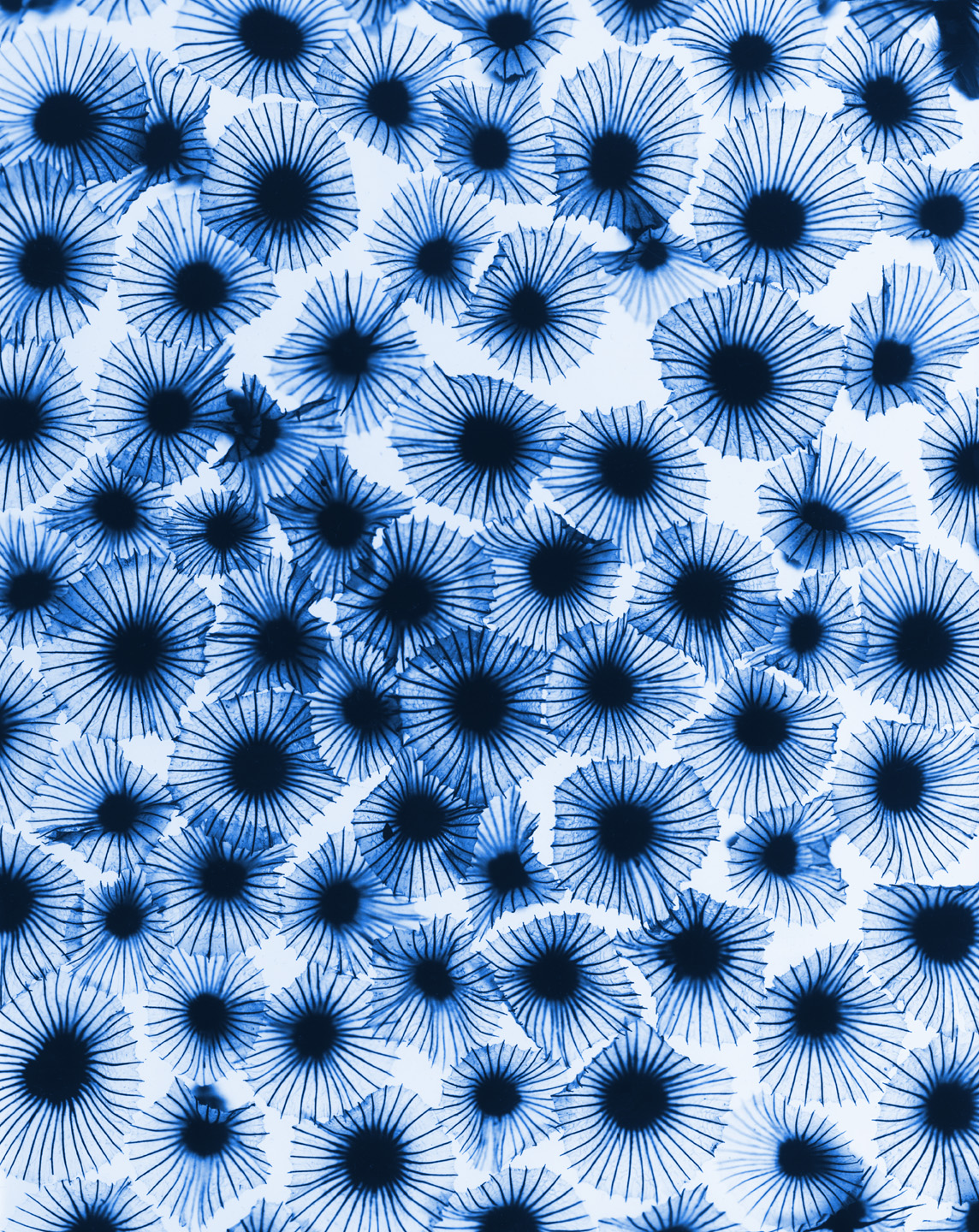

After that brief introduction he walked me over to a wall of his artwork and spoke about the unique technique he uses with plants and plant parts with light exposure. I was instantly intrigued. In some cases I didn't really know what I was looking at until he explained. But the images were captivating in color and the use of plants to add texture, I thought brilliant and a great way to see nature.

Here's my interview with Ron, diving a little bit deeper into his journey in art and his role in this amazing collective, the 3.9 Collective of San Francisco...

RS: …in order to affect change your going to have to be visible to the mainstream. Otherwise how are you supposed to affect change?

RR: Yes, how are you going to get the movement to move?

RS: You can be on the fringe, but for those people have to be out, they have to be recognized by the mainstream. Like the Google buses in SF as an example, it’s a small group protesting but they are very vocal and its to get the mainstream to hear.

RR: So what really interested me in interviewing you is first of all, I’ve always seen art and nature is one. From a background of science research and academia then to now, community organizing…we’re all doing the same thing as we work closely with “environments”.

Let’s bring art into the conversation. I’ve seen your amazing work at the Bayview Opera House with plant parts and photography. I also want to touch on the 3.9 Collective you started in San Francisco.

RS: Well, my background is in landscape architecture, have Masters in this and I’m registered as a landscape architect in California. My Master's is from University of Pennsylvania, and I graduated in ’82, the same year I moved to SF.

I’ve always been interested in nature and plants. As kid I used to go to Georgia to stay with my great aunt where she had property. My family would garden and they had lots of farm animals. I was connected to nature at a very early age and it affected my thinking in terms of careers. But not knowing what landscape architecture really was until my junior year in college. I was originally going to be an architect until I took an elective called Landscape Architecture. So I said, oh I’m going to be a landscape architect and an architect. So applied to both programs; landscaping and architecture and only got into the landscape program. And I’m glad I did landscaping because I found architecture to be way too rigid and I became more interested in being what they call, ‘being a steward for the land’.

I worked for large corporate landscape and architect offices. The last big one I worked for was Skidmore Owings and Merrill; an international firm that built at least 1/3 of SF’s downtown skyline. I was able to work on some really good projects and one big project in SF was on the landscape master plan and urban design of Mission Bay. It was odd to watch it come alive, seeing people occupy this industrial landscape that used to be a train yard. I’ve gotten used to it now and it’s getting more normal now to see people jogging, walking their dogs, strollers, etc..

RR: So that was a fairly recent? Or was it more like the first design of that area because now The Blue Greenway is built?

RS: Yes, actually Mission Bay planning project started in the 70’s and in the first plan, residents in Potrero Hill protested because they didn’t want skyscrapers blocking their view of the Bay Bridge. Then it went to another firm, they did the plan, and Skidmore was hired to review that plan and fine-tune it. After that I left Skidmore in ‘90. In the 2000’s it started developing and there was always the idea to have a stadium and activities right at the entryway of Mission Bay. Mission Bay is about 300 acres of land, its big and mostly landfill.

After I left Skidmore, I did consulting with a firm in Oakland on a regular basis on anything from residential garden design, urban design, and master plans. After leaving them 7 yrs ago, I decided to focus more on residential garden design. And I found that more rewarding because I’m working directly with a client who’s getting the benefits of my services and it’s their private space that they get to enjoy as well. I always work with people who are open to the idea that what I give them is a very flexible design where yes, I can tell you where the paths, plants, and the patios, but understand that this is your yard and you have to change the plants because plants are living things. They change. They’re not going to stay little, they’ll get big and eventually they’ll die and you’ll have to replace them, etc…

So in the Bayview, I live in a development of 125 single family houses where we sit on 17 acres of land and 11 acres of it is landscape and most of the landscape is hills that surrounds development. Being a Landscape Architect, and seeing the property experiencing erosion in places very visible to passers by and homeowners, I informed the board that its time to do some improvements. So for the last 6, almost 7 years we’ve been doing planting to deal with erosion issues. And also by improving the landscape, people are noticing that there are changes happening and they like the beautification and it also inspires them to take think about gardening in their own yards. So again, even though residential, it’s a large scale and I’m used to doing large scale. I try not to think about the scale so much as the planning and at the same time, educate people. We’re trying to get some farming areas implemented. So we planted some fruit trees in hopes of getting some people inspired to help and say, “oh I want to come out and help and do some planting”, but that didn’t happen. But other homeowners on another street expressed interest in doing some gardening so we’re going to put in some fruit trees and work with owners to see what kind of vegetables do they want to grow.

RR: And that’s home. You’re working with your neighbors on your street.

RS: Yes, that’s home. I’ve been in the Bayview since ’85. I moved to SF in ’82. I’m glad I held onto it because property values have gone up.

RR: To put it into context for folks, what did Bayview look like in ’85 and how much change has happened?

RS: Oh, it’s a tremendous amount of change. I mean, the gangs that used to hang out on the street…they’re gone. Now you have old retired people, who are drunk and hang out and have nothing else to do. A lot of the vacant lots that were there are being in-filled with new condo projects. So there’s a new generation of homeowners, but all these new homeowners are all aging. They’re people in 50’s-60’s that don’t want to leave so in order to live in the city they’re looking for affordable housing and the Bayview is one of the best areas. It’s easily accessible to the freeway and downtown so they’ve taken an interest in improving their environment. They’ve taken it to contacting the chief of police to say they aren’t going to tolerate certain things.

There’s been a movement to improve Mendell Plaza, which used to have a street running through it but the city closed it off and people have decided to occupy it and give it back to the people. Some very positive changes happening. There are also younger people coming. Those who live in the city and don’t want to leave, they live in the Bayview. And we’re talking about mostly white people coming to the area because it’s affordable. They can buy a 3 bedroom house in the 500K’s with a garage, backyard, sunlight, option to garden, etc…

RR: Your thoughts on that as far as seeing the change in community in demographics in what we’re seeing now?

RS: Demographics are changing from majority black to majority Asian. So Bayview at one point was in 90% Black and there have always been Asians there. If you look back on records of the early 1800’s, you can see that there were Chinese shrimp fishermen there. The German, Irish, and Italian, were out there. Some of them moved away but they’ve always been there. The Blacks came in the 40’s to work the shipyards here, in Oakland and Richmond. Then those jobs disappeared then things really got bad because then they became highly unemployed. Some one said to me that the largest ethnic group right now is 40% Asian. I don’t know what it is for Blacks, but if you take public transportation, on the T, you can see at any one time, 25% of the riders are black, the rest Asian and White. It’s changed.

RR: In general, SF has a high number of Asians. But in Bayview Asians are increasing more?

RS: Yes, and there’s good and bad to that. The down side is yes, the Black population of SF is leaving but they’re not only leaving Bayview, they’re leaving the Fillmore or wherever they’re located in SF they’re leaving. They don’t feel welcome or that the place supports them. If you feel there’s no community for you, they’re not going to come.

There was a recent article in SF Examiner published about discouraging their black friends from moving to SF. It said, come visit, see it, enjoy it, but don’t live here; you won t get the support you would get living in Chicago or NY and Oakland. So it’s interesting and it's not going to help the city. The city is supposed to be a diverse culture.

And government makes a difference. The city government in Oakland has been promoting and supporting diversity. And they know that supporting Art Murmur is going to be a boon to the city because its part of the culture. If you go to NY, arts are highly supported. In SF, the arts are not supported. Sure, people want to go out and support the opera and they want to support the major museums, but in order to keep those institutions alive they need feeders. And if those feeders disappear its not going to support the greater institutions.

RR: This is a good way to segue into this collective that you started, the 3.9 Collective. Through our mutual friend, Nancy I came to know this collective, but interestingly enough I was also doing a lot of environmental-historical education with an organization in the Bayview/Hunter’s Point neighborhood. So, knowing and teaching more about the history of SF communities and the environmental justice legacies there and also experiencing first hand the sudden changes of demographics in the city, when Nancy shared with me her being a part of this collective as a black artist, I asked her to explain it to me. And she said the 3.9 was in reference to how many black people are left in SF.

RS: Well, in 2010, right before the census came out there was a report in the Bayview Reporter said they were estimating that the black population in SF is going to be 3.9%. And that’s where the 3.9 came from.

There were several articles that came out with projections of declines of 50% and still declining. The official percentage that came out in 2010 said that 6.1% of SF’s population is black. And the thing I find interesting about that 6.1% as their official number and 4 years have past since then, what I’m hearing some of the news reporting, which is surprising, is that they’re been saying that the black population of SF is 4%. But its definitely less than 6% because blacks aren’t coming, they’re leaving. And the ones that are leaving now seem to be moving to the East Bay, but during the first “dot.com” boom in 2000, there were people who inherited their homes from their parents that were there in the 40’s decided it was time to sell. The said, let’s get 700K for our house and move back to the South where our family came from and get a lot more for your money. You know, buy a house with some land and still have some money left over. So there was that “exodus”. There was another exodus of people that took advantage of the subprime mortgages and moved to Antioch, Pittsburgh, etc… because they wanted to get out of Bayview. They did see it as a good environment to bring kids up in. So there was this mass exodus, then we had the tech boom crashed and the leaving stopped.

But in 2000, one of the things that signaled to me that the Bayview had changed, was when I saw a white man, walking down the street wearing leather chaps and walking his poodle. I said, “That’s It! The Bayview has turned a corner and its not turning back!” And its been true! It’s absolutely true!

But cities go through cycles. And the same thing is happening in NY, but you know NY has the outer boroughs where the populations are still supported; Brooklyn, Queens, etc…

It’s been interesting watching this figure get closer to what the original estimate was based on someone else’s report and its not being addressed. I think one of the things that’s come out of this, because there’s this income inequality people realize is going on, is that it’s not just affecting blacks, but all of the working class people in SF. Sure, you can use the Google buses as a symbol but there really needs to be protests to city government officials. The supervisors, the mayor, etc…Those are the ones setting the policies and those are where the protests should really be directed. If you want to affect change, and policy change, the change is happening on the government level. I mean, look at Twitter, they got exemption from their payroll tax and they came to SF because of that. And now there’s a backlash because they’re supposed to give back to the city. And they’re starting to and they have been actually, it just wasn’t getting publicized. So now they’re starting to publicize that, like the volunteer work that their employees are doing. And that was the agreement for them to be able to move into the city, was to give back to the community. But you need the other companies to jump in on that agreement too, like to Google’s and IBM’s, etc…

The employees are young and young people want to be in the city; it’s vibrant. So employers and major corporations are realizing that the intellectual property are in the major cities and they support that. But they also need to realize that the workers that support those environments, like to secretaries, administrative staff, who don’t have tech experience have to live somewhere. And if they’re going to continue servicing them, where are they going to live?

RR: There have also been those communities that have been there a long time and don’t want to be displaced by al lot of that development.

RS: Which is happening to renters. This Ellis Act is just not working. It’s working for developers who want to come in, but for those who have been here for 20-30 years, all of a sudden they have to go.

RR: Given all this change and the pressures on SF communities with this change, how did the 3.9 Collective come about in relation to giving support to the black artist community.

RS: I met an artist, William Rhodes whom I met at and event at the Bayview Opera House. He moved from Baltimore over 4 years ago and he was asking me, “Where are all the black artists because every time I meet a black artist they tell me they live in Oakland?”

And I said, “Well, they’re here in SF, but they’re all scattered.” So he suggested we form a group and that’s how it all started. We started to reach out to the black artists that we all knew. He knew Nancy Cato, I knew Rodney Ewing, he knew Sirron Norris. So it started with the 5 of us and we decided we needed to work on making ourselves more visible by having shows, contacting our networks and spreading the word that there’s a group of black artists in SF who are asking our our existence to be acknowledged. We also wanted it to be a group to be visible to support other black artists who might be in other neighborhoods in SF and might feel isolated. We wanted to provide a support system for folks to talk to people who have experience with the art world in SF and basically form a black community of artists here.

It was interesting because people we knew very well, who live in Oakland, wanted to be part of a group. And we were pretty adamant about saying, “It’s very easy for black artists to get together in Oakland; there are a few communities of black artists there. What we’re really trying to do is to pull black artists in SF together. Sure, we can form alliances with you, but how about supporting all the black artists in SF before they all leave?”

The group grew to about 20 and we continue to do shows. It gets challenging to keep people together because of group dynamics, but one of the things that we wanted to do was more community outreach and work with kids. William is pretty active right now in teaching kids at the Bayview Opera House and is an artist, in their Dare to Dream Program. We’re also at Bayview’s monthly event sponsored by the SF Arts Commission called Third on 3rd. There are always 2 members from the 3.9 Collective out there working with the kids so they can see that there are black artists here in the city to say, “Yes, you can do this. Yes, you need support and yes, it’s difficult doing it by yourself and don’t think you can do this by yourself.”

We want to have this exposure to the black community as well because it introduces them to art. People in general don’t like going to galleries and museums because there’s a certain environment there. So what I’ve started to look at is public art opportunitites. In 2010 I was awarded a commission to do permanent artwork for the new Bayview Public Library, which opened in February 2013.

I realized what I was trying to go after was trying to find a way to reach a broader audience and public art is a really good venue for that. Because people go to libraries and airports, they see art. You can’t not see it. Its very competitive, but I decided to keep plugging away at it. I have work at the Laguna Honda Hospital and also at the Public Utilities Commission new headquarters.

RR: In your artwork, your using plants and plant parts in the darkroom in this very unique technique. Can we get into the technique?

RS: The basic idea is that I’m using silver photographic paper so black and white images are created. However, I don’t use a camera and I don’t use film. I take objects and I lay them directly on the paper and expose them to light. When they’re exposed to light, the object on the paper becomes a white shadow and everything else around it goes black. So you end up with a silhouette. That’s the basic idea and they’re called photograms.

I use plant materials, natural materials, and salt. At the Bayview Library I’ve used salt, water, sugar, and cotton. I wanted to think of things that would connect to the neighborhood and the people of Bayview.

So for the shipyard in the neighborhood, I used water. But I also started to think about, what are we made of? Where did I come from? What am I, who am I? These questions also came about because my mother died in 1998 and I’m an only child and both my parents are no longer alive. Naturally those questions stared to come up and prompt me to start this project. I started with using the human figure first but decided I needed texture. So I looked at the plant world, which I was already familiar with as a landscape architect, and decided to collage the plants with the figure because they are a part of us, we are a part of them.

And because black people were slaves at one point, I decided to use cotton balls as an expression of our past. People may not recognize the cotton in the collage,but I use different things to express our inner being and of our histories as well.

RR: In this broader context of working in the natural environment or using natural materials, how do you see yourself working in this “industry of environmental work”?

RS: As an artist you don’t really think about connecting to other systems or institutions. You think about creating your art first. And that’s what I did. It was about ‘how do I express myself and who I am and where I came from?’ It became more universal. But at the same time, by me focusing on images that are just plant material, I realized it’s also talking about the environment. Because the series I do with plants is called, The Secret Life of Plants, I wanted people to realize that there’s something different about this ‘tulip’ that I’m looking at. Why can I see all of these lines? It’s not that you have to understand what those parts are, but as opposed to looking at a cut flower sitting on a table and you notice it because it looks beautiful or smells good, I wanted people to see the inner aspect of the plants. It’s looking at it at a deeper level. Thereby questioning when you see a rose or a tulip, let me look at it a little closer and see what kind of patterns are in there and get a better idea about nature. And begin questioning the things we take for granted, like nature.

The other day I read that we don’t even know what’s in our oceans. Only 5% of our oceans have been explored. When I read this, I said, you’re kidding me! What do you mean? We’ve gone to outer space and but we haven’t gone to the deepest parts of the ocean?”

So my photography is really there to try and educate people about the environment and take a closer look. You become curious. When I take an onion and slice it and take a photogram of it, you see concentric circles, but people don’t know what it is! Even master chefs will look at the image and question, what is this? You don’t see it because you’re either not looking very closely or you’ll take the food and think about how to put it in your dish, you’re not really looking at the essence what that plant material is.

RR: Or coming from a different perspective. Different people are coming to the image each in a different way. Not a lot of people are used to seeing things through a photogram. But seeing your spread of photogram on the wall, it was fun to try and guess what I was looking at.

You also talked about ‘taking things for granted’. We take the world for granted and how much knowledge we don’t know about the world. Can you speak a little bit more about that feeling of curiosity comes from? We don’t always go there, you know?

RS: I was always a curious child, so that curiosity I had wasn’t squelched. It’s interesting looking at these kids in the Bayview that have these young parents. And they don’t let these kids explore and therefore, they haven’t explored themselves.

I met this young mother who is taking her child to a Chinese school so that he can be exposed to other cultures. And you can tell she really wants him to have more than what she had or has. And she can really see that the city has changed and the world has changed. And if you don’t give kids an opportunity to explore and look a things that are outside of your world, you’re going to be left behind. You’re going to be closed off.

So for me, having that curiosity about life, people, adventures was very natural for me. Not saying that it wouldn’t be natural for other people, but I also think that people have to be exposed to environments that they might not be comfortable with. Simple things, like Bayview kids never seeing the Golden Gate Bridge or Golden Gate Park because their parents never took them there for whatever reason. So, sign your kids up for a day camp where they can go out and be exposed to these things. Because I think kids are naturally curious and they want to go out there. It goes back to the parents. And if the parents can’t do it, there needs to be a mentor or somebody that can lead them in that direction.

For two summers I did a summer camp at the Headlands Center for the Arts. On the other side of that facility is a public

housing development called Marin City. Someone decided to give money to that community so the kids can have an afterschool program. And the kids didn’t know what was just over the ridge, on the other side of the mountain. There’s the Marine Mammal Center, all this science stuff. So, we introduced them to art where we had them write a story and draw pictures about their home life as a way of communicating therapeutically and letting go of this stuff they needed to let go of and share with people so they’re not traumatized.

And also as a plug, I’ll say I have a Master’s degree in Social Work! I was going to work part time as a social worker and do part time photography, but things didn’t work out that way and I ended up doing the landscape design work because it gave me more flexibility to travel and play around with my photography. So it’s been interesting that I’ve been able to come full circle back to the thing that I really like a lot. I like helping people. The 3.9 Collective is still talking about who we can collaborate with to do art programs to expose kids to professional artists.

RR: Well, I appreciate having your perspective on your work in the environment. Your photogram images are really speaking for it self when I see it and now that I’ve been able to sit here and have a conversation with you. So, thank you for sharing this with me and everyone who’ll be reading this story!

To find out more about Ron and his artwork, please visit:

Press Release for Bayview Public Library